Music Teacher Reaches Autistic Kids Through Rhythm

The student and the teacher sit facing one other, their feet on the drum pedals, drumsticks in their hands. Autism may make the ten-year old’s speech unique, it may make his attention variable, but right now he is communicating with his teacher in a different dimension, in a language he can feel.

“Can you go from there back into the beat?”

“I got you.”

And the ten-year-old lays down a funk groove with panache, does a fill around the toms and then leans back into the groove, accenting the off beats as his face settles into a quiet, confident smile.

The teacher laughs and hits the rim of his snare drum. “You rock!” The kid grins.

There is no more basic proof of being alive than our own heartbeat. From the rhythm of our cells anticipating day and night, caused by the rotation of our planet, to the seasons moving in rhythm with the circling earth, from the rhythm of our breath, rhythm is what connects us to each other, our entire existence has a pulse, even the rhythm of our vibrating vocal cords allows us to connect with one another. But our hearts falter for children who struggle to make this connection. The number of children diagnosed with autism in the 1980s was one out of every 2,000 children. Today, the CDC estimates that one in 150 8-year-olds in the U.S. has an autism spectrum disorder, or ASD. Words may fail them, but there is another way for kids to communicate, to connect in another dimension.

Scientists may be baffled, but music teachers are connecting to neurodivergent kids with rhythm. Kids, parents, and teachers are finding out that music therapy is an excellent way for ASD kids to learn to communicate and feel more confident. This is happening all over the world. A study by graduates of music therapy at Ewha Women’s University in Seoul, South Korea, says, “For individuals with ASD, music interventions have been found to generate favorable outcomes in social attention, social engagement, initiation of social interaction, and emotional reciprocity.” ScienceDirect.com says, “Rhythm provides therapeutic benefits for autistic children. Rhythm and music help develop social-communicative skills.”

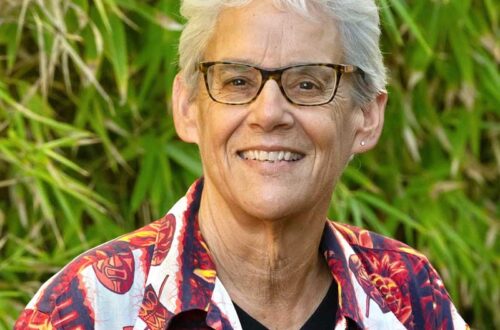

I sat down with Dirk Stockton, master drummer, and founder of a rhythm-based music school in Sacramento.

Richard: Why use drums to connect with neurodivergent kids?

Dirk: The behavioral therapy industry gets a lot of work with autistic kids. I almost took a job working for a company doing that as a behavioral therapist, but it was this system where the autistic kids are dehumanized and trained like dogs. They give them a treat when they do the right thing and act “normal.” And when they act neurodivergent, they don’t get their treat. And what this does is to train inauthentic and uninformed human behavior that would cripple someone who’s not even neurodivergent. Or removes them further from neurotypical people and how they see the world.

The cool thing about our approach is it’s not about external standards and rewards, it’s about intrinsic standards and rewards. The kid knows their own, true path when they find it. When they are walking their path, they know it. Like all of us, when we’re walking our path, we know it.

Having a conversation in a different dimension

Parent Sara Jukes says, “Two of my kids have severe ADHD. I’m grateful for Dirk, who understands different ways to love and communicate with neurodivergent people.”

Dirk: Having a conversation in a different medium, it’s a different dimension. When educators help kids by reading stories to them, they transport them to another dimension where they learn a lesson. And that’s what drumming is like. It’s a dimension that is just as communicative as spoken language, but more abstract. So, the abstraction is like a bridge. A bridge between minds. I have students that I haven’t heard talk for two years. I have students who I’ve never heard talk.

Richard: How do you interact with a student who doesn’t talk?

Dirk: Autonomy is my number one principle. If the kid won’t do anything, I ask them what we should do. I ask them what I should do. A lot of the time, they’ll run the lesson. I have a kid who comes in and he says 30 minutes or 60 minutes. At the beginning of the lesson, I don’t know how long it’s going to be, it’s arranged with his parents. The kid hardly says anything and that’s his control of the environment.

“First we learn how to break a stick, then we learn how not to break a stick.” – Dirk Stockton

We are all from Africa. One of the first technologies we invented, an ancient, primordial technology, was used to create our own rhythms. It was used to communicate, to share news and information, used to gather people together, used to prepare us for battle, used to prepare us for love and used to prepare us for the grave. This one instrument completely and immediately connects us all, it can at once be the easiest instrument to understand and the most demanding to master.

Richard: How does consistency and structure play into this?

Dirk: A lot of autistic people like repetition and consistent, reliable structure. They want to come back to the same room with the same-colored walls and look at the same music stand on the same side. My students will mention really small details that have changed that make them uncomfortable.

“The amplifier was facing the other way last time.”

And they won’t even say why or question it. They just say it. They’re just saying it because they’re thrown by it. And you know what? Everyone’s like that. We all like consistency.

Richard: How do you introduce new material?

Dirk: I used to throw new exercises at students a lot. “Hey everybody, we’re studying Mozambique this week!” I still sprinkle it in, but lightly. I built some advanced Latin patterns, foot patterns, and I just put the sheet music up on the stand and said, “Well, this is difficult. You don’t have to do it if you don’t want to. It’s an advanced piece.” I emailed it to everyone, kind of baiting them, and every student said, “I’ll give it a shot.” They all studied it because I didn’t challenge anyone to do it.

Richard: How is this effecting the kids?

Dirk: They get some swagger. We’re working on all of the students to up their drip and riz. They’re looking pretty drippy. Some of the students have grown out their hair. Sometimes I come out and talk to the parents while the kids are drumming, I have relationships with all the parents. And they come to me if they seek guidance on something specific.

Richard: What might a parent say who comes and goes, “Hey, Dirk, we need help with this”?

Dirk: Some students have embraced their autonomy by locking themselves in a basement and playing really hard for hours and hours. The parents like it, but they also ask me about it. Sometimes parents think it’s so important to get in there and hear what’s in that basement, but it’s not. That’s the kid’s adulthood forming. Keeping me and the parents out of the basement is key.

Richard: With your private, in-person lessons, the kids join you in a closed room, and there’s a camera on you, and the parents are in the next room watching the lesson on a computer screen. And with the camera on you, you can shut the door, as opposed to having the door open.

Dirk: Right. Sometimes the door is open, but it’s loud, and drummers do need to consider the neighbors. You do have to contain the volume. Sometimes, for the first couple of lessons, parents may want to come in and stand behind me. Then they realize it’s personal, and they don’t want to disrupt it. Watching it through the monitor in the next room, they get to observe their kid opening in ways they’ve never seen before.

Richard: The parents sit on a couch, watching the lesson on-screen. Do the parents talk about your monitoring system?

Dirk: They love it. They say it’s the best television show they’ve ever seen. They don’t want to miss any of it.

Richard: What happens after the lesson?

Dirk: When the lesson is over, the student and I come out and the kid stands at attention, with military drumline posture. The parents then ask, “How’d it go?” And I report on how it went. Sometimes it leads to serious talks about being honest with your family.

Richard: Can online drum lessons achieve these breakthroughs that you get in person?

Dirk: The online lessons are really good. They aren’t as good as in-person lessons. There’s no argument for it. But if you don’t have someone around that can teach at the level you need, online classes are great. I teach online students that just signed up to be online. Completely online.

Richard: Often neurodivergent people like repetition. They want repetition. One aspect of drumming is it is repetitious. Is there a relationship there?

Dirk: I think it comes back to the same argument. What else runs on repetition? The wheel. The days and nights. The stock market. The planet. Everyone likes cycles. That’s why everyone likes drums.

Not everyone has to face the same way

Richard: You’ve taught children who were said to be autistic.

Dirk: Yeah. Some of them come from government organizations that assist families with autistic kids with funding and other services.

Richard: I have a buddy with an autistic son. When we were introduced, the young man couldn’t face me. He had to face away.

Dirk: I think it’s important not to put labels on autism. Just like it’s important to not put labels on age groups, and races, and all the other stuff. Because it’s such a wide, wide range. To say an autistic person faces north, and normal people face south… It’s easy to miss someone’s character because you’re putting a definition on them. You’re assuming that they act a certain way because of some biological or neurological predisposition, when really, they’re just someone that acts that way. It has nothing to do with who faces north and who faces south. That’s just how they are.

I get to observe miracles.

Dirk: I think that the beauty of the service is, I never interface with parents on their child’s challenges. I don’t collect any of the reports from the people who have diagnosed them as autistic. I don’t ask the parents where they are on the spectrum or what disorders they have. I have no record of any of their medical stuff. Or any of their psychological stuff. It’s an approach to connecting with people that works well because I don’t try to analyze what makes them autistic. I just work with them on their drums.

Richard: What effects do you see on the kids?

Dirk: Oh, they are opening up. Their families become proud of them, so impressed by their skill. A lot of these families have never had anyone in their family play music, it’s completely foreign to them. They come in so worried about their kid and then they see they’ve got this child prodigy. I get to observe miracles.

Parent Ryan Fuhrman says, “The experience with Dirk has been revolutionary for our son. In less than 2 years Dirk has shaped him from a kid with no musical experience to drumming for his school band.”

Richard: In the end, what matters most?

Dirk: Knowing that the kids are so special, that it’s a higher order of importance to keep them emotionally safe. I teach all ages, some in their 60s. All the people I teach that are older have some history of a teacher who crushed something in them that they’re now nurturing from a sapling. It’s a heroic effort to nurture that sapling that got stepped on. It would be a lot easier if we stopped criticizing new artists so heavily. From a teacher’s perspective, and from an audience’s perspective, if everyone could give the squeaky clarinet a little slack, music would bloom and get better. Everyone would feel better. It’d be easier for me to teach. Encourage the musicians. If they sound bad, encourage them more. It’s encouragement that will get them there, not discouragement.

Dirk Stockton is a music mentor who has been playing and teaching professionally for over 20 years. He teaches all styles and skill levels, with a focus on expression, composition, and personal growth. He supports percussion training and performance for local high school drumlines, jazz ensembles, theaters, and private studios. “I specialize in neurodivergent studies and love working with unique clients who may not be getting the tailored support they need.” For more information about Dirk’s in-person or online work, contact him at: [email protected]