Independent Schools Review

Independent Schools Serve the Whole Child

By Suki Wessling

At these independent schools, there’s a helping hand next to every potential crack, waiting to give a student a hand up.

January is our Independent Schools issue, and every time I write an article for this issue, I’m reminded of my own family’s search for education that suited our kids’ needs. At one point another parent said to me, “We’re just sending our kids to the neighborhood school; we’re not picky about education.”

But it isn’t always pickiness that sends parents looking for alternatives—it’s necessity. Although we often talk as if most kids are some imagined “average” student, all of us come to education with our own special needs.

“For whatever reason, there’s a systematic desire to keep this box and try and fit everybody in it,” says Mom of the Month Carmen Clark (check out our article!). “We’re noticing with neurodivergence, this isn’t just one or two kids in the classroom—it’s half the class!”

When I interviewed the educators quoted below, I asked them to define “special needs” more broadly than an individualized education program (IEP) that children with identified special needs receive in schools. We all bring our needs to school with us—what are those needs and how can we serve them?

Chartwell: Kids bring an IEP…and more

Chartwell school (chartwell.org) only serves students with diagnosed language-based learning differences (LD), but they know that their students walk in with a lot more baggage than their diagnosis.

First of all, says Jodi Amaditz, Director of the Lower and Middle School, kids don’t just walk in with one disability. “It’s how your brain is wired. Students with dyslexia often have impacted working memory so that plays into math, holding information, auditory processing, following directions.”

Shane Whitman, a Lower School Homeroom Teacher, sees that students come in with their disability, but also a self-image formed in response. “They look like they’re expecting to struggle. They don’t expect to have any friends, to do well in school, they have a lot of negative talk in their own mind.”

Once students are taught with a method adapted to their learning needs, Shane says, they blossom. “I can see their confidence grow, they sit up straighter, they volunteer in class more often—you can see them maturing as a person just by finding out what their strengths are.”

Chartwell offers students the tools they need to show their strengths academically.

“Generally, students with dyslexia are simultaneous processors, big picture thinkers—they have trouble with putting things in order,” Jodi explains. “I taught [some students] how to take their ideas and use a mind mapping program. It just kind of blew the kids’ minds. This one student said, ‘Why hasn’t anyone ever taught me this before? This is life-changing!’”

Chartwell also acknowledges that students who seem to compensate for their LD in a mainstream school are carrying a burden they shouldn’t have to carry.

“It’s exhausting to have to work that hard,” Shane explains. “Even if they are doing well, they shouldn’t have to work ten times harder than the other person, when there’s a way, working a regular amount like everybody else.”

Jodi says that in the end, the most important part of the student experience at Chartwell is that the staff really sees the children and understands them. “[The students] realize that the staff also struggles and thinks and learns differently, and that we celebrate that here.”

Delta: Trauma-informed teaching

Delta Charter High School (deltaschool.org) was intentionally started as a small school to serve the needs of students who are not succeeding in traditional schools. As the student population has shifted, the school stayed true to its mission.

“Our goal is to provide really strong relationships so students feel safe to take risks and try new things and to give school another shot—when they’re considering not coming to school at all,” explains Jen Ra’anan, principal/superintendent. Although the school originally served students who were severely at-risk, the student population now features a mix, including students with social-emotional disabilities, with untraditional learning needs, and students who want to do advanced work at Cabrillo more quickly.

Just like any public school, Delta has a resource team for the students who have diagnosed LDs. But Jen says that a lot of modifications in a typical 504 Plan are already served by the school’s approach—“We’re kind of a 504 school.” The small environment has most accommodations built in.

Jen points out that some traditional ways of dealing with students who are not meeting expectations actually encourage the students not to try at all. For example, Delta teachers don’t dock points for late work because they emphasize the importance of getting the work done no matter what. Life skills like organization and time management, which so many students struggle with, don’t affect grading, and all students get a tutorial period with a teacher who has access to records that show outstanding work in their classes.

“Speaking from a trauma-informed place, when you ask students to take responsibility [for missing work], they can’t do it,” Jen explains. “Building those relationships takes time.”

Trauma-informed practices are extremely important at Delta, where, Jen explains, students coming from stressful educational experiences “get really good at hiding.” Students at Delta, every one of whom gets interviewed by the principal when they apply, find that they can’t hide anymore.

“When we look at our data, we notice that anxiety is at epidemic proportions,” Jen points out. “I tell my staff: You treat everyone who walks through this door like they have trauma.”

She admits that having such a flexible program can be difficult. Delta accommodates everything from students’ work schedules, to being a safe space for LGBTQ+ students, to providing distance learning when students experience mental health issues.

“Aside from my own child, they’re the most important people in my life. If there’s a railroad track, I’ll lay down on it!” Jen says. “My goal when my students stand up [to give their graduation speeches] is to hear them say, ‘I did this. You helped me, but I did this’.”

Diamond: Where students learn to identify what they need

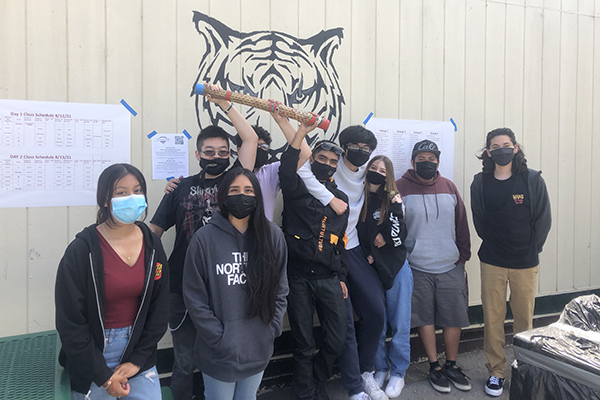

Diamond Technology Institute (dti.pvusd.net) doesn’t seem like a school for kids with special needs. It’s a small charter school focused on Career Technical Education (learn more about CTE by searching “career technical education” on our website). Students at Diamond are required to complete five career pathways—humanities, digital media arts, agriscience, engineering, and entrepreneurship.

“The goal is for them to explore and figure out what they want their next steps to be,” explains principal Marci Keller. “Not one Diamond Tech graduate graduates without a plan A, B, C.”

Marci explains that the school’s approach is based on FAIL: First Attempt In Learning. “I call it vigor instead of rigor. If something is vigorous, it doesn’t mean it’s not difficult and students don’t struggle a little bit in their learning, and that’s OK.”

Every single student at Diamond has an ILP—individual learning plan. Students themselves look at their own data and present to a teacher team each year to update their plan.

Academic needs are only a part of each student’s plan.

“I have a student whose father passed from Covid,” Marci says. “I have a student whose parents weren’t vaccinated and she was stressed about coming to school because she didn’t want to get it at school and bring it home.”

A lot of Diamond Tech students live in multifamily homes where there is no space for study, so the school provides in-school and afterschool opportunities for homework. Marci says that many students have parents going through divorce or other problems at home, and a good number come to school hungry, not knowing when they’ll get their next meal.

The school serves the need, whatever it is.

“It’s layers and layers,” she says. “A lot of kids have PTSD right now. Social media impacts them at a faster rate than it used to before, for good or for bad. They have a lot of information coming at them much quicker than they used to.”

Marci is quick to point out that research on small class size is not clear. But what is clear is the importance of seeing and connecting with students as individuals.

“It’s the small community of educators, of the students themselves that connect, the ability to create a culture that you can’t create on a big campus.”

Whatever need a student brings in the door at Diamond Tech, they find a community there to meet it. “It’s more like family instead of, ‘Like, I go here’.”

Alternative Family Education: Learning designed for the individual

AFE (sccsbssc.ss8.sharpschool.com/schools/afe)is a small school with a big mission: to provide a personalized education for each and every student who enrolls. Based on the Branciforte Small Schools Campus, learning programs range from pure homeschooling with a parent to a patchwork of classes, including online, private, community college, and even single courses at mainstream high schools.

Homeschooling offers nontraditional students an important benefit, according to AFE teacher Nancy Aylsworth. “Time is one of the big components of homeschooling. What you can accomplish in a half an hour is so much more than a two-hour class.”

Because of that, AFE attracts an unusual variety of students: professional athletes and performers, students with a single deep academic passion, students preparing for a nonacademic career who need a diploma, students with serious illness, and more. Some students never come to campus, meeting once a month with their teacher to guide their work.

But most students take part in the vibrant community events taking place on the tiny campus and abroad. The school offers academic courses, clubs, clay studio, field trips, and sports—all taught by teachers, parents, students, or community members.

Homeschooling ranges from “school at home,” where families follow grade-level curriculum, to “unschooling,” where students themselves determine what and how to learn. Most students, however, fall into the category of “student-led learning,” which may include formal curriculum, but is much more flexible to suit students’ needs.

“[Students with serious health issues] can come and participate when they’re able,” Nancy explains. “Or they can stay home and take care of themselves when that’s what they need to be doing. We don’t have a ‘take attendance, oh, you’re not here today’ kind of thing.”

Because each student’s education is individually designed for them, almost any special need can be accommodated.

“All of our students have a plan that’s geared towards them,” Nancy says. “But we do have a higher percentage than a typical public school population with an IEP because our classes are small and flexible. Students can make connections more easily.”

Finally, it’s those connections that lead us into the conclusion that all of these educators shared when I asked him what they had learned about education by working at their small schools.

All schools can do some of what small schools do

Shane and Jodi at Chartwell would like to see all schools emulate their focus on social-emotional learning and early identification of LDs. “How you’re feeling inside is going to impact how you do in school,” Shane says. Jodi would like to see more comprehensive teacher education about learning differences.

Marci at Diamond points out that assuming that all students develop at the same rate leaves behind many students who shine at her school. “Humans grow at different times. Just because a student in ninth grade doesn’t have, for whatever reason, what they need to master [a subject], there should be opportunities down the road.”

Several teachers mentioned the small size of their schools, and recommended that large campuses be reorganized into academies or other smaller learning groups.

Nancy, whose school is on a campus organized in that way, points out that AFE’s greatest strength is that the students are known and recognized: “As a teacher I know all the students who come on our campus. Even if I don’t work with them directly, I’m there to call them by name, to recognize them. In a small community, students are there to recognize each other, call on each other, welcome each other. It makes students feel safer, feel like there is a place for them.”

Finally, Jen at Delta points out what all of these educators have seen in action: “One adult in a child’s life can change the trajectory of that person’s life. My goal would be to identify the students who are struggling—those are the students who slip through the cracks.”

At these independent schools, there’s a helping hand next to every potential crack, waiting to give a student a hand up.

For deeper conversation on this topic: Please visit https://tinyurl.com/GrowingUpIndSchools2022 to listen to each of these in-depth conversations!

Suki Wessling is a writer and educator living in Santa Cruz County. Read more at www.SukiWessling.com.

You May Also Like

January 2022’s Mom

January 1, 2022

Stress Busters

January 1, 2022