Teacher’s Blog August 2018

By Tiffany K. Wayne

High school History and Government teacher, Mount Madonna School, Watsonville

I am anticipating the start of the new school year and missing my students. The last time I saw most of them was on Friday, May 18th, our last day of academic classes.

Finals exams were over but I still had one more day of classes with my 10th grade U.S. History students before they left for a week-long science trip to Catalina Island to study Oceanography. We had started the film, Selma, a few days earlier as an end-of-year movie.

“That made me cry,” a student shared, wiping her eyes with her shirt. “Why did they have to kill Jimmie Lee Jackson? For no reason!”

We talked about the ugliness of racism and violence in our country. I told the class that I was born the same year Martin Luther King, Jr. was assassinated: 1968. They stared at me in awe, as if their teacher had just time traveled and appeared to them from out of the past. “None of this was that long ago,” I tried to tell them, but these are 21st century kids and 1968 is ancient history.

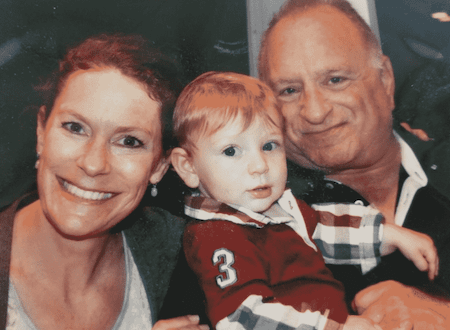

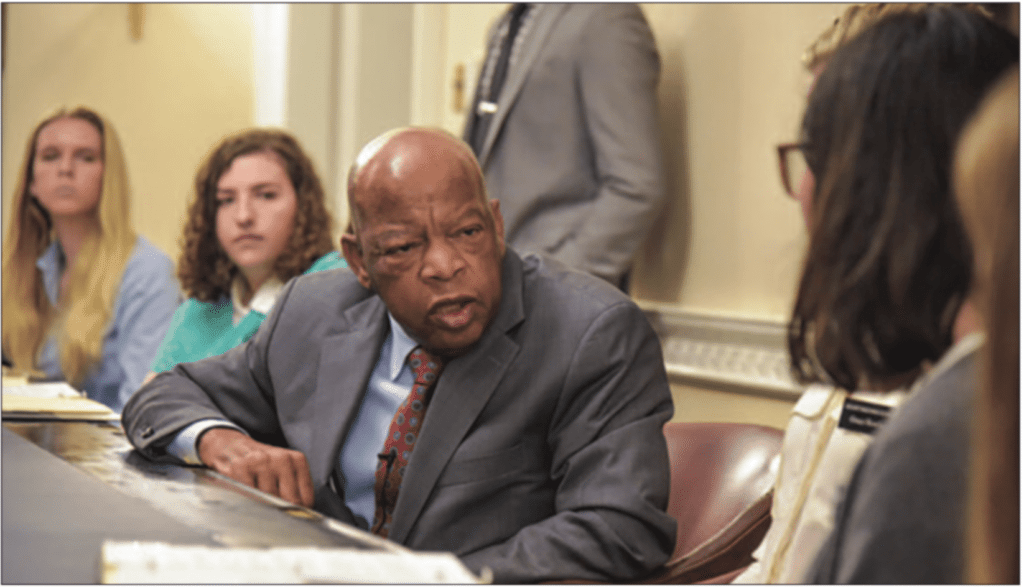

One of the reasons I chose to show Selma to this class was that our current juniors and seniors (including my own daughter) were on a class trip to Washington D.C. at that very moment and had met Congressman John Lewis just that week. We pulled up the trip blog and projected their schoolmates’ words and photos on the whiteboard.

One of the students – a senior who had previously sat in my history and government classes – reflected in his blog post on his emotional meeting with John Lewis:

“When I asked John Lewis my question about how we could keep our moral principles in times of crises, he looked me in the eyes the entire time he gave his answer, the same eyes that “saw the face of death” on Bloody Sunday in Selma, Alabama….he wanted so desperately to pass on this message to the youth of the nation, the message of non-violence, love over hate, and importance of community. “

It wasn’t that long ago. It’s happening now.

“I hope John Lewis is still in Congress when we go to D.C.,” one of my sophomores said, inspiring her classmates to excitedly start calling out names of other public officials they might want to meet in person:

“Ruth Bader Ginsburg! Actually, I’d want to meet any Supreme Court Justice.”

“Trump! I have some questions for him.”

“I want to meet the Parkland kids.”

The Parkland kids: the new generation of student activists.

After the movie, the class is dismissed to lunch and I spend the afternoon grading and cleaning and organizing my classroom, before leaving it for the summer. Throughout the afternoon students wandered in and out as they finished up art or writing projects in other classes or have free time to play volleyball outside.

While her classmates run about outside in the quad, one student sat quietly at a table across from me, flipping through her phone.

“Don’t you want to go outside – or do something?” I said, in my accusatory kids-today-always-on-their- phones adult voice. She ignored my question.

“Tiffany, did you hear the news? there was a school shooting in Texas this morning.”

Yes, I had briefly seen the headline when I logged onto my email earlier that day but, honestly, I just did not want to think about it during the school day. Those of us who teach, work at, or attend high schools do not have the luxury of avoiding thinking about what has become a regular news onslaught of school shootings. Just two months earlier I had stood outside with these same students as we held a 17-minute silent vigil for the victims of the Parkland, Florida high school shooting.

Was it selfish to want to get through this day – this last day of classes – without having to process another unfathomable event?

“This is so scary!” the student cried out, holding her phone out for me to see.

I had just talked kids through crying over the death of Jimmie Lee Jackson in 1965. I had been touched by their empathy for people in the past, but it turned out history and the distance of time were no comfort. This is the reality of the world they are growing up in now.

“Yes,” I told her. “I saw that in the news, but we don’t have all the details yet.”

I wanted to wait for details, but she was getting the details as they came in a live update. She was visibly shaken.

“Hey,” I put my hand over her hand that was holding the phone. “Let’s wait until we know more and then we can talk about it. Want to help me file papers?”

Just weeks before the Parkland shooting we, like schools across the country, had one of our classroom lockdown drills. The sheriff’s department had met with faculty and told us that the lockdown procedure had changed: We were no longer to shelter in place, hoping the shooter skips our classroom. The new state protocol for an active shooter lockdown is Run, Hide, Fight.

Realizing that it is not always possible or safe for a room full of 20-30 kids to just huddle and wait in a classroom, we are now told to evacuate to a safer location, away from the buildings. If we are unable to leave our room, we should then barricade in place and, if in imminent danger (i.e. the shooter has entered the room), actively resist. Disrupt his plan, throw things at him (books? sharp pencils?), fight back. At our faculty meeting, we tried not to imagine how a confrontation between children and an automatic weapon would play out in this scenario.

Realizing we can’t actually practice fighting off an armed gunman, for our lockdown drills we just practice awareness and staying calm. Lock the door, close the blinds, silence or turn off cell phones. Resume quiet study activity until we get the signal or code from the staff outside the door. The drill is not stressful or panic-inducing, but it is also not particularly reassuring.

The teenagers joke about who runs the fastest and about the heroics they will perform to save their friends. Others – buoyed by the self-esteem and nurturing environment of parents and teachers as much as by teenaged bravado – are sure they can outsmart or outwit the shooter. But I know there are too many possible scenarios and too many unknowns. I feel lucky that I don’t have to do this with kindergarteners.

Run, Hide, Fight.

Another student skipped into the classroom to tell me that they were making tamales and enchiladas and salsa for their last day of Spanish class. Many of this group of students travelled to Costa Rica with this trusted teacher over the summer.

A student complained that a classmate put too much cinnamon in the mole sauce.

“I still want to taste them,” I said, despite the warning, and headed to the school kitchen.

The mole was fine – a little spicy from cinnamon, but also sweet and flavorful. I took a plate of enchiladas back to my classroom.

The student who was watching her phone for updates on the Texas school shooting was still there, while another girl, her friend, was flipping through a paper magazine, one of several subscriptions I keep for the social studies classroom. The students can – and do – access many of the same subscriptions online. With a paper copy, however, they are more likely to land on something that interests them or catches their eye, not just read an article I assign.

Today, this student is looking through UPFRONT, a New York Times-based current event news magazine for teens.

“Look at this photo, Tiff. This is terrible.”

She holds up an article about gun violence with an image of thousands of pairs of children’s shoes displayed by activists in D.C.

The issue of the magazine was dated May 14th. Four days before the next school shooting.

“Every one of these shoes represents a kid who has been killed by guns. You can’t even count them all.”

“I guess that’s the point,” I say.

Students moving about by their own choice and interests between volleyball, cooking, video production, watching films, reading magazines, or chatting with the teacher. Why can’t school be like this all the time?

But these conversations and interests and relationships with the teachers have been built through days in the classroom, days of rigor and structure, of reading and analyzing and mastering information, days of following through on a difficult project, collaborating with people you might not normally collaborate with, putting things into context and seeking and finding connections.

“There are eight students dead in Texas now,” reports the girl with the phone watching the news updates. Later we learn that two teachers were also among the victims.

Friday, May 18, 2018: the last day of school before my students were off on other adventures for three months. I have missed them and I can’t wait to hear all about Catalina Island and Costa Rica and family vacations and surfing and summer jobs and summer flings. They will tell me all about science camp and art camp and their hopes and dreams and plans toward futures. They will reunite with friends and share stories about a summer that their peers in Parkland, Florida and Santa Fe, Texas did not get to have.

Lucky kids.