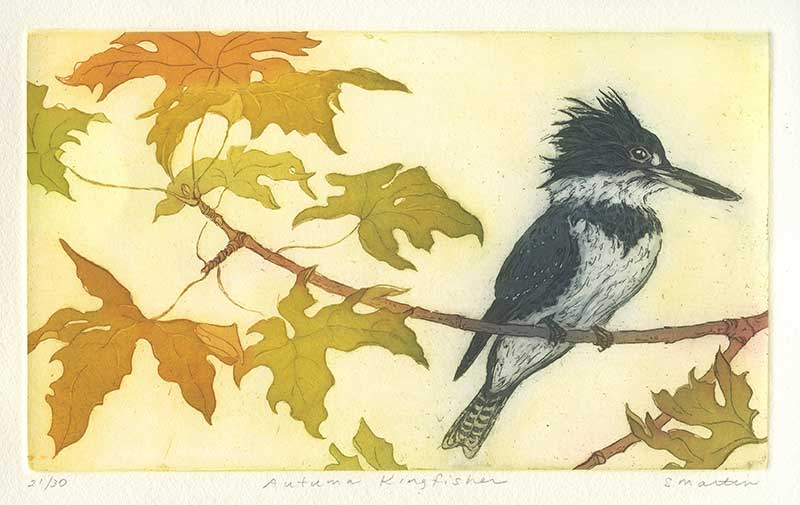

Stephanie Martin is a well known painter and printmaker based in Santa Cruz. Her beautifully hand-colored etchings depict the wildlife of her native landscape. Martin’s illustrations are part of many Bay Area collections and publications, including Fruit Trees for Every Garden: A Organic Approach, by her husband, Orin Martin, manager of UCSC’s Alan Chadwick Garden.

How did you discover etching?

SM: I fell into etching by pure chance: it was offered in the evening! I was in my mid-40s, working as an elementary school teacher, and interested in a new challenge. I enrolled in Introduction to Drawing at Cabrillo, and the following semester found an Intaglio Printmaking (etching) class offered in the evening. I rushed to class after my day job and was soon smitten by the process. The Advanced Etching class at UCSC met at night, so again the scheduling gods were in my favor.

What is the appeal of this medium?

SM: Printmaking is seductive. There are so many processes involved in etching and printing a plate; there are steps which demand great concentration and strategizing, and there are more meditative repetitive tasks. I like that balance. Because so much equipment is required, printmakers generally work in shared studios. The tight-knit community that arises in the studio is another wonderful aspect. Printmakers are always game to share techniques and advice, commiserate your failures, and celebrate your successes.

Your etchings often spotlight plants, flowers and birds. How did you choose your subjects?

SM: I have always been enchanted by California’s avifauna and its wild and cultivated flora. Nothing gives me more pleasure than observing a plant or bird in the wild, taking the time to study it closely, and sketching it. I learn so much about the organism and get lost in wonder. I winnow through my sketchbook to select the images that are compelling enough to develop into an etching. Is the pose interesting, the composition satisfying? Will this be better suited as a black and white or color image?

When I portray a bird, whether it is a songbird or a diving falcon, I need to imbue it with life. I’m not entirely sure what animates a piece–partly it’s about getting the eyes right–but I know when I have succeeded. (Or failed: not all etchings cross the finish line.) Plants are also inevitable subjects for me. I gravitate to California native flora, but when my horticulturalist husband or daughter bring home a persimmon branch or an amazing cultivated poppy, how can I ignore it? Plants have the advantage of being more sedentary and easier to sketch from life. I have leeway with composition and design; I can change the size or orientation of a stem or leaf, whereas a bird’s parts cannot be revised.

Briefly explain how the etching process works.

SM: Once I’ve settled on an image and composition, I start the process of etching the plate. First I coat a polished copper plate with a waxy “ground”, and scribe through that coating with a needle tool. I immerse the plate in acid, which eats away the exposed areas to form channels that will hold ink and print as lines.

The next process I use is aquatint, which is a way to create areas of tone on the plate. It is rather tricky but I love the effect it gives, looking like one has painted with watercolor or ink wash. After a plate is etched successfully, I rub ink into the textures and wipe it off the surface. The inked plate is covered with damp paper, a wool blanket, and run through a press.

I often work in color, and inking those plates is an exercise in patience, as I hand apply one color, wipe the excess, and continue with the next color. All the colors are printed in one run through the press. Because of the hand work involved in every print, they are all slightly different.

To enjoy etching, you must be willing to give up some control. While I have a vague notion of where I am heading with an image, the process itself has its own will. I feel that every plate is a test plate. The acid might etch some unexpected textures, or an idea might come to me mid-process that changes my direction. There are wonderful effects you can get in etching that no other medium can create.

What do you strive for in the final result?

SM: I have a high regard for my subjects, and hope that my art conveys this. I want an etching to inhabit a life of its own and bring the viewer into a state of wonder. Why does this bird have such a penetrating gaze, or ridiculous crest on its head? That delicate-looking warbler with slender legs and beak: do you know how tough this bird actually is? It migrates thousands of miles every year. The stamens draping from a Boxelder tree in February are as interesting to me as the rare bird perched on the branch.

My other aim is to get my audience excited about the curious process of etching itself, and pass the torch, so to speak. The world of printmaking is vast and varied, and etchings occupy a sweet little niche in that world.

By Christina Waters